ABOUT YOSHI

Yoshi Kubo (1914-1997) was a birthright American citizen of Japanese ancestry who lived in Ballico, a rural town in California’s Central Valley. When Yoshi graduated from high school in 1933, he bought farmland in nearby Cortez, becoming the first in his family to own land, as a consequence of California’s Alien Land Law (1913), which barred Asian immigrants from buying property. His farm was associated with a Japanese American agricultural cooperative known as the Cortez Colony, established in 1919 to circumvent that prohibition.

Yoshi was an avid fisherman who would head for the water whenever he could find an excuse to step away from the farm. Despite his affiliation with the Cortez Colony, he was deeply engaged in traditional American pastimes. A genial and gregarious fellow, he lent a hand on the local fair committee, was active in the gem and mineral society, and played center field on his community baseball team, the Cortez Wildcats, which was coached by his best friend, Hilmar Blaine. Uncommonly well-read for a small-town farmer, Yoshi had a treasure trove of poetry committed to memory by literary giants and social activists like Langston Hughes, and would eventually turn his hand to writing a bit of poetry himself.

When Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, it took the Kubos by surprise. Until then, the war had been a remote rumbling in the news, not something they felt they needed to concern themselves with as they went about their lives in rural California. But suddenly Yoshi and his family were plunged into an atmosphere sizzling with xenophobia and rumors of drastic measures to come. Ten weeks later, on February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the removal and relocation of all persons of Japanese descent in proximity to the west coast—even those with as little as 1/16 Japanese ancestry. Over 120,000 innocent people were to be forced from their homes, businesses and farms. Two-thirds of them were American citizens, and half of them were children.

The Army began the eviction and confinement of Japanese Americans 33 days later, compelling evacuees to quickly sell, lease or store everything they owned, as they were permitted to bring nothing more than what they could carry. With just six days’ notice, Yoshi and his family were evicted from their farm and incarcerated indefinitely, first penned up at the Merced County Fairgrounds in cramped, filthy horse stalls, and then imprisoned behind barbed wire patrolled by armed guards at the desolate, windswept concentration camp known as Amache in Granada, Colorado. Meanwhile, land speculators fell upon the highly productive and meticulously-managed Japanese farms like locusts. Only through his swift decision to entrust the preservation of the farm to his friend Hilmar could Yoshi hold out hope that his land and livelihood were not lost to him forever.

In early 1944, the draft classification of young male internees was abruptly changed from “enemy non-alien” to “eligible for combat duty.” Concerned for his family’s welfare if he were conscripted and bitter about being stripped of his land, Yoshi refused to acquiesce to conscription against tremendous pressure from both the government and his own community, arguing that as a farmer, he should be eligible for an agricultural deferment to serve the war effort by farming his own land, a draft classification his white neighbors back home were readily given. He and the 21 other Amache draft resisters maintained that they were not opposed to military service, or to the draft. They considered themselves loyal Americans. Rather, they believed that the conditions under which they were being drafted were contrary to the principles of American democracy.

One by one, the resisters were arrested and brought before the federal court in Denver. Yoshi helped organize their defense, conferring with civil rights lawyers and organizing a common defense fund to which each of the men contributed $120, enough to pay all their court fees and engage a sympathetic local attorney. But each and every one of them lost their case, as the judge assigned to the trials allowed no evidence or argument to be presented beyond the simple question of whether or not the men had attended their preinduction physicals.

This courageous stand resulted in Yoshi’s incarceration in the Tucson Federal Prison Camp (aka Catalina Federal Honor Camp), where he and his fellow prisoners of conscience from the Topaz, Poston and Amache concentration camps broke rock to build a mountain road while bonding over their shared convictions, calling themselves “The Tucsonians.” When not performing hard labor, Yoshi passed the time with writing, including a poem he titled “We Are But Refugees,” in which he laments the injustices being perpetrated by his beloved nation. In his journal, Yoshi revealed that he lived by the maxim “row, don’t drift,” choosing the path he felt was right, even though that choice came at great cost.

Ultimately, Yoshi was reunited with his family and returned home to discover that all was not lost—his friend Hilmar, to whom he’d entrusted his property, had been a stalwart caretaker. Yoshi and Hilmar remained close their entire lives, and Yoshi’s family, emotionally scarred but unbroken, thrive upon their land to this very day. But the vast majority of the internees were not so lucky, finding their leased and stored property stolen, ransacked, vandalized, occupied by squatters or liquidated by the government, and facing an onslaught of racism and exclusion from those they had once considered friends.

In 1947, Yoshi and all of the 292 Japanese American internees who had been handed felony sentences for draft resistance during the war were pardoned by President Truman. Although Truman had no sympathy for conscientious objectors whose resistance was based on religious or moral grounds, he recognized the principled civil disobedience of the Japanese American internees who refused to answer the call to service while they and their families were still unjustly imprisoned, in violation of their Constitutional rights. But the resisters would have to wait another half century before their own community recognized their principled opposition and celebrated them as civil rights leaders, rather than ostracizing them as disloyal draft dodgers. The Japanese American Citizens League finally issued an apology from their community to the resisters they had long treated as a shameful secret in 2002.

For decades in the Japanese American community, there lingered a cloud of humiliation, guilt and trauma around memories of the internment, and many refused to discuss their experiences with their children. Even more opprobrium shadowed those who had taken their own principled stands in deciding to resist conscription, rather than choosing, as many Japanese Americans did, to serve the military effort by applying their language skills in intelligence in the Pacific theater, or fighting with great distinction in the European theater, even as their families were still unjustly imprisoned by their own government. Although Yoshi was unusually open about his wartime experience in the camps, for many years he remained silent about his felony conviction and prison sentence. Even as he and his brotherhood of Tucsonians met annually for five decades to bond over their shared adventures in civil disobedience, the next generation of Kubo family members knew nothing of Yoshi’s prison sentence. Only when Yoshi’s son Dan began his own lifelong journey of social activism as a student at San Jose State University, speaking out against the Vietnam War and agitating for the creation of one of the nation’s first Asian American Studies departments, did Yoshi finally feel ready to reveal to him the full compass of his own story.

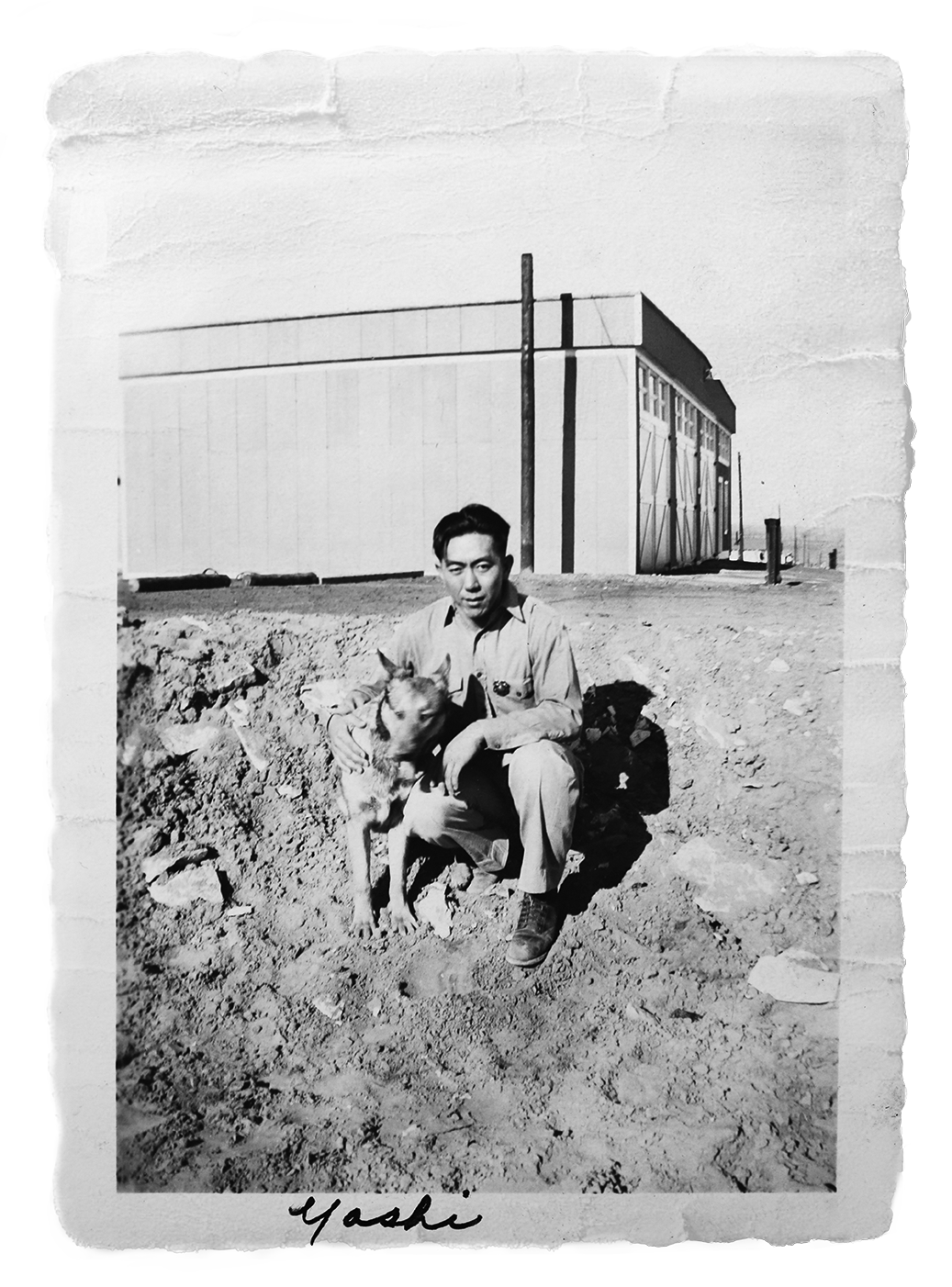

Photos TOP to BOTTOM: Yoshi with dog, Yoshi at home, Yoshi and his wife Louise July 1947, Kubo family at Merced Assembly Center August 1942, Yoshi seated third from left in the front row at Ballico school 1924.